Benutzer:Shi Annan/Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China

Vorlage:Short description Vorlage:Italic title

The Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (or the Gujin Tushu Jicheng) is a vast encyclopedic work written in China during the reigns of the Qing dynasty emperors Kangxi and Yongzheng. It was begun in 1700 and completed in 1725. The work was headed and compiled mainly by scholar Chen Menglei (陳夢雷). Later on the Chinese painter Jiang Tingxi helped work on it as well.

The encyclopaedia contained 10,000 volumes. Sixty-four imprints were made of the first edition, known as the Wu-ying Hall edition. The encyclopaedia consisted of 6 series, 32 divisions, and 6,117 sections.[1] It contained 800,000 pages and over 100 million Chinese characters,[2] making it the largest leishu ever printed. Topics covered included natural phenomena, geography, history, literature and government. The work was printed in 1726 using copper movable type printing. It spanned around 10 thousand rolls (卷). To illustrate the huge size of the Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China, it is estimated to have contained 3 to 4 times the amount of material in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.[3]

In 1908, the Guangxu Emperor of China presented a set of the encyclopaedia in 5,000 fascicles to the China Society of London, which has deposited it on loan to Cambridge University Library.[4] Another one of the three extant copies of the encyclopedia outside of China is located at the C.V. Starr East Asian Library at Columbia University. A complete copy in Japan was destroyed in the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.

One of Yongzheng's brothers patronised the project for a while, although Yongzheng contrived to give exclusive credit to his father Kangxi instead.

Name[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China is known as the Gujin Tushu Jicheng (chinesisch 古今圖書集成, Pinyin Gǔjīn Túshū Jíchéng, W.-G. Ku-chin t'u-shu chi-ch'eng) or Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng (chinesisch 欽定古今圖書集成)[5] in Chinese, also translated as the Imperial Encyclopaedia, the Complete Collection of Ancient and Modern Illustrations and Texts, the Complete Collection of Ancient and Modern Writings and Charts, or the Complete Collection of Illustrations and Writings from the Earliest to Current Times.

Compilation[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Kangxi Emperor hired Chen Menglei of Fujian to compile the encyclopedia. From 1700 to 1705, Chen Menglei worked day and night, writing most of the book, including 10,000 volumes and around 160 million words. It was originally titled the Compendium or Tushu Huibian (图书汇编). By 1706 the book's first draft was completed, and the Kangxi emperor changed the title to Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (Gujin Tushu Jicheng). When the Yongzheng emperor ascended the throne, he ordered Jiang Tingxi to help Chen Menglei finish the encyclopedia for publication by around 1725.[6]

Outline[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The 6 series are as follows.[7]

- Heavens/Time/Calendrics (历象): Celestial objects, the seasons, calendar mathematics and astronomy, heavenly portents

- Earth/Geography (方舆): Mineralogy, political geography, list of rivers and mountains, other nations (Korea, Japan, India, Kingdom of Khotan, Ryukyu Kingdom)

- Man/Society (明论): Imperial attributes and annals, the imperial household, biographies of mandarins, kinship and relations, social intercourse, dictionary of surnames, human relations, biographies of women

- Nature (博物): Procivilities (crafts, divination, games, medicine), spirits and unearthly beings, fauna, flora (all life forms on Earth)

- Philosophy (理学): Classics of non-fiction, aspects of philosophy (numerology, filial piety, shame, etc.), forms of writing, philology and literary studies

- Economy (经济): education and imperial examination, maintenance of the civil service, food and commerce, etiquette and ceremony, music, the military system, the judicial system, styles of craft and architecture

The six series in total are subdivided into 32 subdivisions.

Note that a pre-modern sense is intended in both "society" (that is, high society) and "economy" (which could be called "society" today), and the other major divisions do not match precisely to English terms.

Gallery[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Part 1: Heavens/Astronomy[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

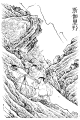

Part 2: Geography[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Territories

-

Map of the Qing dynasty's east coast (Mongolia and Taiwan marked as 蒙古 and 臺灣, Ryukyu and Korea marked as 琉球 and 朝鮮)

-

Further inside China (Chengdu marked as 成都 and the northern desert marked as 沙漠)

-

Map of Shanxi

-

Map of Guangdong

-

Map of Jiaozhi (Vietnam)

-

Map of Fujian

Borders[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Kingdom of Sicily (Southern Italy), transcribed as 斯伽里野

-

Ma'ata (麻阿塔國), possibly referring to Malta, located in the Mediterranean Sea

-

Image of person from Kalingga Kingdom in Java (大闍婆國)

-

Srivijaya (三佛齊國)

-

Kingdom of women (女人國), recorded in travels during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, possibly referring to some part of Australia. It is mentioned in the History of Yuan and was described by the Yuan dynasty traveler Wang Dayuan.

Part 3: Society[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Human Affairs[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Describes some anatomy of the human body

-

Diagram of human body

-

Liver diagram

-

Dragon

Imperial Harem[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Palace Doors, Harem

Imperial Perfection[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Part 4: Nature[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Image of Nüwa

Plant Kingdom[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Ranunculus sceleratus (石龍芮)

Part 5: Philosophy[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

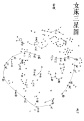

Canonical and other Literature section[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Page from the Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China

-

Guhe diagram (古河圖)

-

Hetu Shengchengtu (河圖生成圖)

-

Fuxi (伏羲) diagram

-

Qiankun (乾坤) diagram

-

Tiandiji number diagram (天地极数图)

-

Bagua trigrams

-

Xingtu (性图) with calendar dates

-

Odd numbers: 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, etc.

-

Parity: even and odd numbers

Education and Conduct[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Fuxi's Taijitu

Study of Characters[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Wang Yingdian liuyi tujie (王應電六義圖解)

Part 6: Economy[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

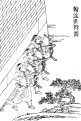

Military[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Punishments and blessing[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Nine star diagram (九星图)

Food[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

See also[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

References[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Citations[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Sources[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Search for Modern China, Jonathan Spence, 1990.

External links[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 故宮東吳數位古今圖書集成 etext

- WorldCat

- Archive.org

- HathiTrust

- An Alphabetical Index To The Chinese Encyclopaedia

- WorldCat

- Google Books

- [1] web.archive.org Fehler bei Vorlage * Parametername unbekannt (Vorlage:Webarchiv): "date" Fehler bei Vorlage:Webarchiv: Genau einer der Parameter 'wayback', 'webciteID', 'archive-today', 'archive-is' oder 'archiv-url' muss angegeben werden. Fehler bei Vorlage:Webarchiv: enWP-Wert im Parameter 'url'.

- [2]

- Library of Congress

[[Category:1725 non-fiction books]] [[Category:1726 non-fiction books]] [[Category:18th-century encyclopedias]] [[Category:Chinese culture]] [[Category:Chinese encyclopedias]] [[Category:Qing dynasty literature]] [[Category:Sinology]] [[Category:Chinese literature]] [[Category:Leishu]] [[Category:Kangxi Emperor]]

- ↑ Ku-chin t'u-shu chi-ch'eng (Completed Collections of Graphs and Writings of Ancient and Modern Times). npm.gov.tw, archiviert vom am 25. November 2010; abgerufen am 25. Juli 2012.

- ↑ Tony Allen, R. G. Grant, Philip Parker, Kay Celtel, Ann Kramer, Marcus Weeks: Timelines of World History. First American Auflage. DK, New York 2022, ISBN 978-0-7440-5627-3, S. 176.

- ↑ Fowler, Robert L. (1997), "Encyclopaedias: Definitions and Theoretical Problems", in P. Binkley, Pre-Modern Encyclopaedic Texts, Brill, p. 9; citing Diény, Jean-Pierre (1991), "Les encyclopédies chinoises," in Actes du colloque de Caen 12–16 janvier 1987, Paris, p. 198.

- ↑ Introduction to the Chinese Collections. Cambridge University Library, archiviert vom am 23. Dezember 2012; abgerufen am 25. Juli 2012.

- ↑ Endymion Porter Wilkinson, Scholar and Diplomat (Eu Ambassador to China 1994–2001) Endymion Wilkinson: Chinese History: A Manual. Harvard Univ Asia Center, 2000, ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4, S. 605 (englisch, google.com).

- ↑ Benjamin A. Elman: On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550–1900. Harvard University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-674-03647-5 (englisch, google.com).

- ↑ An alphabetical index to the Chinese encyclopaedia ... Chʻin ting ku chin tʻu shu chi chʻêng. 1911.